How to identify and support someone at risk of suicide

Trigger/content warning: This article discusses suicide, death, and substance use.

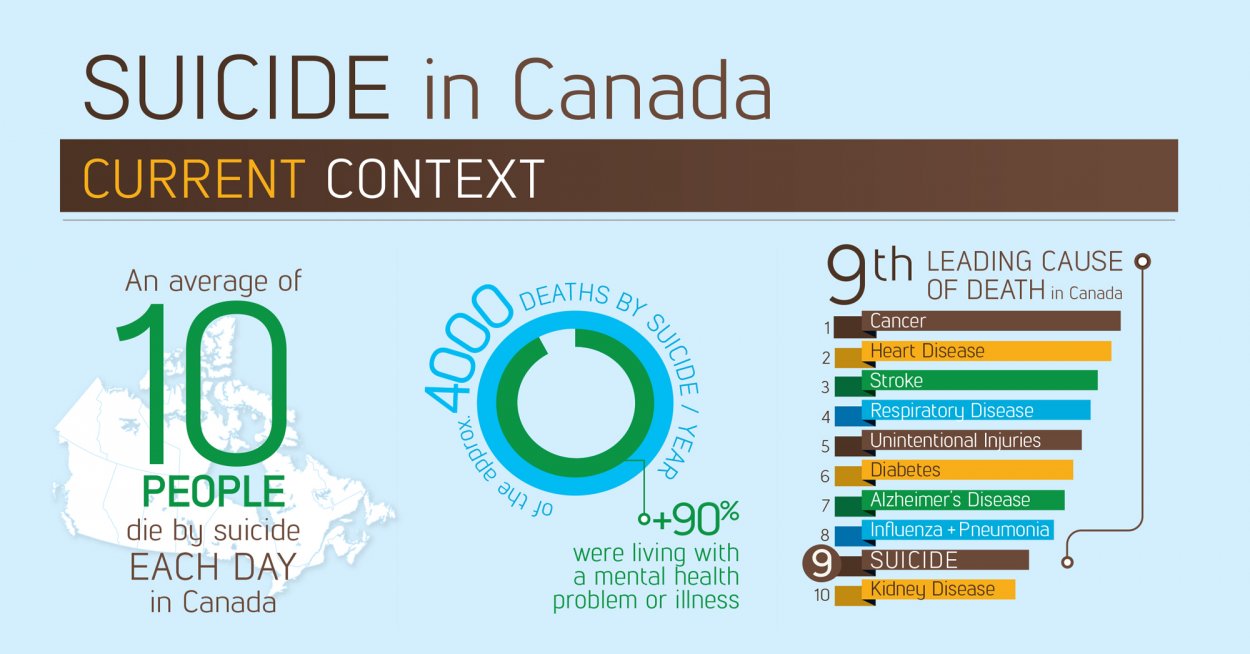

According to Statistics Canada, an average of 10 Canadians die by suicide each day—or about 4,000 deaths a year.

Those statistics precede COVID-19 and while the pandemic’s impact on suicide rates is still uncertain, early research suggests more Canadians have reported suicidal thoughts, says the Mental Health Commission of Canada. Indeed, registered psychologist Dr. Paul Jerry says the pandemic has exacerbated mental health issues such as social anxiety and depression.

“COVID is always in the back of our minds now. It’s like an unfinished task that you keep putting off but is always there,” said Jerry, a professor in the Graduate Centre for Applied Psychology program at Athabasca University.

“If you already have some aspect of anxiety or depression, you use a lot of energy just to get through your day. Now that energy is put towards the pandemic and associated concerns, and you’re even more depleted than you were at the end of a typical day.”

World Suicide Prevention Day

Sept. 10 is known globally as World Suicide Prevention Day, which mental health professionals like Jerry regard as an important step in continuing the conversation about death by suicide. By openly talking about suicide, we can help identify the signs that someone is struggling and offer ways to provide support.

According to the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH), in any given year, one in five Canadians experience a mental illness or addiction problem. Jerry noted that the social anxiety associated with the COVID pandemic has substantially impacted people’s mental health.

“There are people who want to die and there are people who don’t want to live,” explains Jerry, who has 32 years of experience as a clinical psychologist. “The people who want to die, it’s unlikely that you’ll stop them. The people who don’t want to live just need someone to help them find a way out of their tunnel vision.”

If you think someone in your life may be at risk of a suicide crisis, there are a number of ways that Jerry says you can help.

Suicide in Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada

What can you do if you know someone is struggling?

First, if you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call 911.

The second thing to consider, according to Jerry, is to analyze whether you are the right person to talk to the individual experiencing a crisis. Be prepared and consider the following three points:

- While you may be the person most immediately available, it’s also possible the crisis may be too close to home, or you could be the problem.

- If they say yes to wanting help, do you have the capacity to help them?

- If you’re not the best person, who can you find to help immediately?

“As you start to help, knowing that there are resources out there—and you don’t have to solve the problem and take on their pain—is crucial,” said Jerry.

RELATED: Mental health check-in for AU learners

“There are people who want to die and there are people who don’t want to live. The people who want to die, it’s unlikely that you’ll stop them. The people who don’t want to live just need someone to help them find a way out of their tunnel vision.”

– Dr. Paul Jerry, psychologist and AU professor

How you can help

If you are worried, it’s worth talking about. Whether you are in crisis or someone close to you is at risk, crisis lines are the fastest and easiest way to get assistance.

If you do speak to someone you’re concerned about, be blunt but caring. If people joke about suicide, do not take it lightly, Jerry advises. Use language such as, “I know you’ve always joked about this, but I’m worried one day you may actually do it. Would you be willing to talk to me about this?”

Crisis Services Canada states that if you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, reaching out and sharing your thoughts and feelings can reduce stress and isolation. This can help you or the person at risk understand options available.

Warning signs of suicide

Identifying a suicide crisis can be challenging. Crisis Services Canada suggests looking for these warning signs:

Talk or threats to harm oneself

- can range from, “I wish I wasn’t here,” to, “I guess if I was gone you’d miss me/see how good I was for you/would finally understand …”

- off-hand comments like, “I bet this knife would cut right through my wrist,” or, “I wonder if the airbags would really save me if I drive 120km/h into an overpass pillar?”

- “I have enough meds saved up now that I could go any time I want …”

Looking for ways to kill oneself

- Google searches about methods

- talking about recent or famous suicides and how they did it

- considering different methods and their effects

Talking or writing about death, dying, or suicide

- talking about recent or famous suicides

- writing about death, talking about dying, apparent curiosity about how one dies, etc.

In all cases, individuals at risk of suicide are likely to show a change in patterns or behaviour.

Less obvious signs to watch for

Increased substance use

- drinking more, drinking differently (e.g. switching to hard liquor from beer)

- using more, trying new substances including high-risk drugs (e.g. fentanyl)

Feelings of helplessness or hopelessness; no sense of purpose in life

- think Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh. Nothing is fun, nothing is worth the energy, nothing tastes good anymore.

- there is no joy and lots of “why bother” comments

Anxiety, agitation, or uncontrolled anger

- more irritable and upset

- might show as taking risks with insulting others who may be prone to strike back

Unable to sleep—or sleeping all the time

- In the absence of shift work: staying up late because you can’t sleep, then sleeping through the day (a reverse of the “normal” sleep cycle)

- Feeling like you’re wearing a lead suit—arms and legs and body feel so heavy it’s easier to lie down than to move; exercise increases fatigue instead of energizing you

Feelings of being trapped, like there’s no way out

- unable to see solutions to problems (except dying)

- tangled logic about why there’s no point in trying (pessimism). “They’ll only ignore my contributions like they always do, so there’s no point in trying.”

Withdrawal from friends, family, and society

- a pattern of avoiding, cancelling, or no-showing for events, video/text chats, etc.

- decreased attendance at family, church, service club, sport events, etc.

- less interest in the world, news, etc. “Why does it matter?”

Acting recklessly or engaging in risky activities, seemingly without thinking

- picking fights with people likely to do damage

- reckless driving (look for dents and unexplained damage to vehicles, or unreported accidents)

Dramatic mood changes

- goes from okay to very sad

- the biggest factor is going from very depressed to happy again. This is often because the person has settled on dying as their best solution and it is experienced as very freeing

“As you start to help, knowing that there are resources out there—and you don’t have to solve the problem and take on their pain—is crucial.”

– Dr. Paul Jerry, psychologist and AU professor

Mental Health Resources

Check out these mental health resources: