What you need to know about vaccine boosters, passports, and COVID testing

COVID-19 misinformation is everywhere. An AU health researcher and nurse helps set us straight.

We have all watched the non-stop news coverage and social media debates about COVID-19 vaccines and related restrictions that have rolled out, been relaxed, and modified.

The deluge of information—and misinformation—has made it difficult to know who or what to believe.

“COVID-19 has been exacerbated by the darker side of social media, which has spread so much misleading information,” says Dr. William Diehl-Jones, an associate professor at Athabasca University (AU). “Regardless of what vaccination you got, you have a high degree of protection. That needs to be one of the most important messages being shared, in addition to the fact that they are safe.”

Diehl-Jones is biomedical researcher with a doctorate in cell and molecular biology and a background as a registered nurse. Throughout his academic career, he has made it his mission to make people better-informed consumers of research and medical news by sharing evidence-based information about vaccines.

“COVID-19 has really exacerbated by the darker side of social media, which has spread so much misleading information.”

– Dr. William Diehl-Jones, associate professor at Athabasca University

Unfortunately, that’s been particularly challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the biggest problems, says Diehl-Jones, is that people are turning to social media and YouTube for information instead of reputable sources such as Health Canada, the Center for Disease Control, and the World Health Organization.

To help differentiate between fact from fiction, we spoke with Diehl-Jones to learn more about vaccine boosters, passports, and COVID-19 testing.

To boost or not to boost? Why vaccine boosters work

While information about the vaccines has evolved since they became available, more recently debate has focused on vaccine boosters—an additional shot or “boost” of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Although vaccines do not always lose their effectiveness over time, it’s not entirely unexpected either, Diehl-Jones says. With COVID-19 vaccines, booster shots might be needed to improve their effectiveness long-term, he says.

The science about some COVID-19 vaccines shows that the body’s antibody response starts to wane over time, making some vaccines less effective.

New information about the Pfizer vaccine shows antibody response diminishes after about eight months, although it is still highly effective at preventing hospitalization and serious illness. COVID-19 boosters, Diehl-Jones says, would function similar to other vaccine boosters, like the tetanus and measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) shots.

“One of the reasons why boosters are used in general is that we want to increase the number of memory B-cells that stay in your blood,” he explains. This helps the body produce antibodies that respond when met with a spike protein, which is one of the surface proteins on the virus.

“This [vaccine] helps the body produce antibodies that respond when met with a spike protein, which is one of the surface proteins on the virus.”

When or how often COVID-19 vaccine boosters should be given is still unclear. In Canada, at the time of writing, only those over the age of 75, frontline health-care workers, and people considering international travel can receive booster vaccinations, although the latter varies by province.

Diehl-Jones says the science is still evolving and Health Canada has not made clear recommendations on when to administer boosters.

“We don’t know what the long-lasting immunity is because the data is still developing. After three or four boosters, will we have immunity for years? We don’t know that yet.”

Will vaccine passports make restrictions unnecessary?

A vaccine passport provides proof of immunization for the COVID-19 vaccine. These passports, implemented provincially across Canada, allow businesses and services to open their doors only to patrons who have been vaccinated.

While passports allow for resumption of more “normal” routines, Diehl-Jones says it’s important not to conflate them with vaccine mandates.

“The purpose of these passports is to protect the public and open up certain activities. We do know that vaccinations and masks are highly effective in short-circuiting the cycle of viral propagation,” he says.

“People may choose to not vaccinate, and with that decision, it should be remembered that there are consequences, such as being unable to travel, attend concerts or eat at a restaurant.”

Recently, the federal government announced proof of vaccination will be required to travel by air or train. The U.S. also announced plans to open the border to vaccinated Canadians.

These types of measures could eventually help win over the vaccine hesitant, Diehl-Jones says.

“When people realize their choice will have consequences in terms of what they can and cannot do, this will hopefully turn the tide.”

“When people realize their choice will have consequences in terms of what they can and cannot do, this will hopefully turn the tide.”

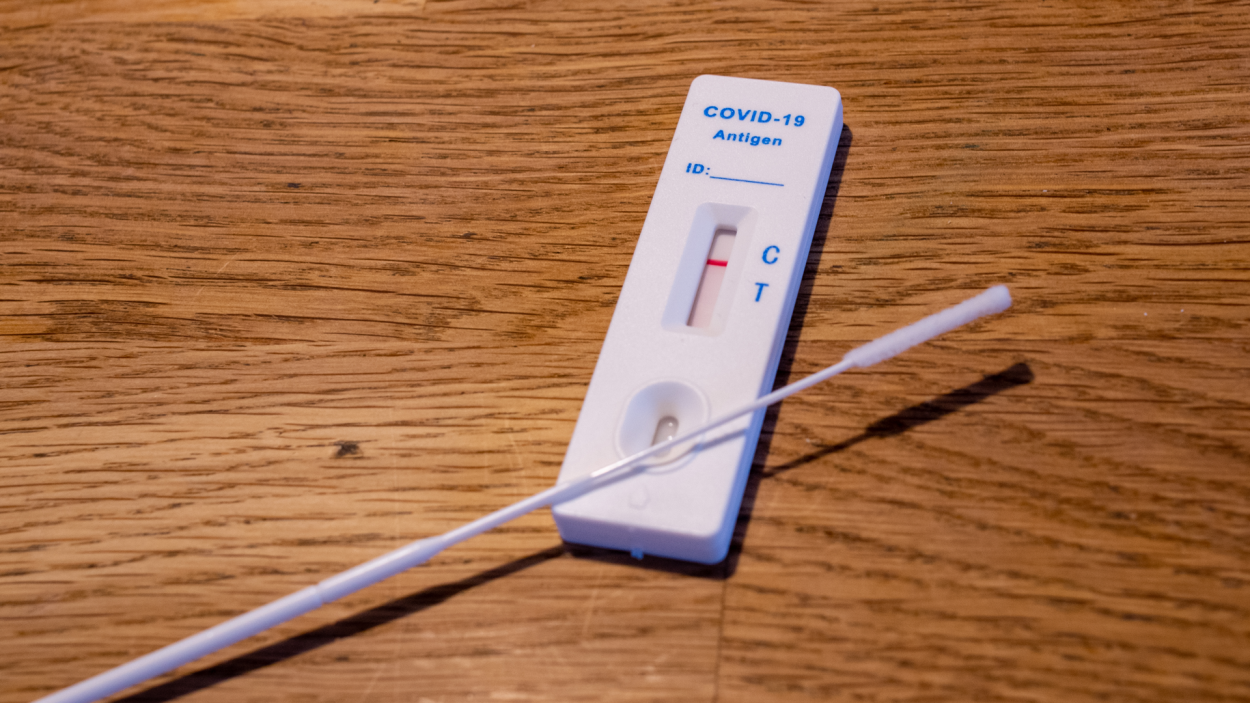

Should I get a PCR or rapid antigen test?

Many businesses accommodate unvaccinated individuals if they provide proof of a negative COVID-19 test, which can be expensive.

According to Diehl-Jones, rapid antigen COVID-19 tests have a few advantages over polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in that they’re cheap, quick, and less invasive.

Rapid tests involve inserting a swab into the nasal cavity for five seconds. An antibody test then determines if any viral antigens are present.

“It suffers the disadvantage of not being as sensitive as PCR tests,” Diehl-Jones explains. “The numbers vary, but it is around 70 per cent accurate. It mostly depends on what stage of the infection you’re in.”

In comparison, a PCR test detects small quantities of viral DNA, is more expensive and invasive, but also more sensitive, explains Diehl-Jones.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) COVID test

Is there an end in sight?

According to Diehl-Jones, that’s a complex question. The best-informed guesses are that COVID-19 will be with us for a long time, but as an endemic, meaning localized to specific area or country rather than a pandemic.

If jurisdictions can increase vaccination rates and the public follows basic public health orders such as getting vaccinated, wearing masks, and social distancing, additional lockdowns will become less likely.

Recently, Diehl-Jones notes that Pfizer has presented very encouraging data regarding the safety and efficacy of their vaccines for children between five and 12 years old.

“Eventually, we shouldn’t be in the position that we are now, which is overwhelming health-care facilities,” he says.

“We’re currently seeing that this is a pandemic of the unvaccinated.”