AU professor Michael Lithgow talks politics and poetry in his second book collection

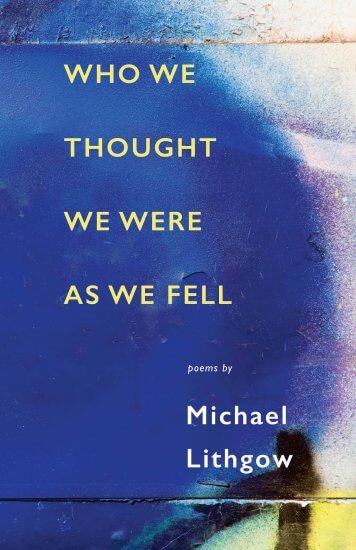

Athabasca University (AU) professor and poetry writer Dr. Michael Lithgow presents the second book of his own collected poetry, Who We Thought We Were As We Fell.

In this interview with fellow AU professor Dr. Evelyne Gagnon, Lithgow reminisces on the process of writing this second collection, the role of politics in poetry, and how in this collection he addressed the tension between poetics and politics more directly than in previous work, allowing him to merge his political ideas with the more intimate nature of his poetry. Lithgow views his poems like windows—or portals—separating and yet linking two different orders of reality. The title of the collection was changed to its current name during the pandemic as the original title had become unfitting, with Who We Thought We Were As We Fell better reflecting a sense of sudden, uncontrollable changing subjectivity.

The book will be officially launched at an online talk and discussion with Lithgow celebrating the book’s release on May 11, 2021, hosted by the book’s publisher, Cormorant Books and Glass Bookshop. To register for the book launch visit the Eventbrite page.

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

In your first collection, Waking in the tree house (2012) the poems were more intimate. In this current offering, we find intimate reflections entangled with political concerns. I’m thinking, for example, of the poem: “You can take these summers”, which is a beautiful family portrait, but you find this political stance in it. And this other poem: “Remembering getting away with”. How do you conceive this intervention of societal or political stances in the fabric of the poem, which is something new if you compare the first collection and the new one?

I have a background as an activist. I was a journalist, activist for about 15 years, so I spent a lot of time thinking about and participating in social movements and forms of critique of Canadian society. So that’s been a part of my world and my world view since I was 20, basically. But I have generally always had a firewall between my political work and the work I do with poetry, because whenever I tried to write a political poem, it wasn’t very good. I had a lot of trouble with it. In this collection, it’s the first time that I’ve been able to encounter these tensions directly. I think what makes it difficult in a poem for me is that the poem is so intimate, and this kind of engagement with the conditions of my own privilege almost has to be a violent rupture. Because, of course, I can’t extricate myself from the conditions of my own privilege even if I want to destabilize them. And yet I have a deep feeling about the problematics of power in the problematics of hegemonies in the way they destroy people’s lives. This is the first time where some of these ongoing concerns—I’ve been able to approach them with the kind of intimate vulnerability that I want in a poem. I think that’s why they’re here in this collection. I think there’s a maturing in my politics and a maturing in my writing, where that firewall that kept those spaces apart is increasingly artificial. I have to come to understand my own vulnerabilities in political terms, and I have come to understand political ideas in terms of the human intimacies they are necessarily nested in.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

I really like this phrasing – thinking about the problems of power, but with an “intimate vulnerability”, I really like that idea. I think it sums up a lot of this collection or part of it, especially those poems we talked about. In many poems we see the speaker at a window in his house observing and musing on the world, commenting on what I could call this disturbing strangeness of a suburban life and the fragility of the present times. Can you speak about this recurrent motif of the disturbing strangeness of the suburban life throughout your collection? Because it evokes many other topos such as the family versus the neighbors, the domesticity, but also capitalism. It is also a space of introspection for the speaker.

I recently—in the past 5 years—moved to a suburb. I mean, I grew up in suburbs, but, you know, once I was out of them, I haven’t lived in suburbs for many, many years. And now I find myself not only living in a suburb, but as a homeowner. It’s a brand-new condition in my life.

When we first moved into this neighbourhood—we’re comfortable here now—but when we first moved in, we were on edge. The suburbs are a strange environment. When you’re more familiar living in more densely populated urban settings, the suburbs are bizarre. There’s a kind of hollowness to a suburb. It’s like: where are the people? Where is the life? Where are the stores and the cafes and the bars? And it’s filled with green space, but it’s not really green space either, is it? It’s like—even though in Edmonton we do have coyotes and wild hare, so it’s a little more wild here than maybe in some other cities—but it’s green space that sustains a very small animal population. It’s still ruled by human values, human economies, human politics, the imposition of human infrastructure on it. In some ways, suburbs are nowhere. They’re not either this or that. So I did feel quite alienated. That tension of alienation in this space, I think that’s where some of those observational poems emerge from.

And it’s interesting, you mentioned the introspection, because there’s something very lonely about living in a suburb. Because you don’t step out onto your street and encounter the hubbub of the world. You step out on the street and you encounter a kind of nothing—a few pine trees and grass and squirrels and somebody walking a dog. There is a lot of opportunity for the kind of introspection that solitude brings, I find, living in a suburb, despite the fact that it’s, you know, an urban space.

As for the guy looking through the window—that’s interesting. I haven’t thought about my work like that, or that particular theme. But what it makes me think about is that a window is like a portal. It reveals a difference between two realities or two different ways to organize reality. Windows are really quite magical. The idea of looking through a window as a portal into another world, that reminds me of what many of these poems are and what poetry is for me. I find myself living in quite a banal world, filled with a lot of chores and tasks and frustration and, you know, all the things that our lives are filled with. And yet beyond this veneer or within this veneer or whatever the verb is, there’s tremendous beauty and tremendous savagery and tremendous, you know, terror and awe and all the sort of the magical stuff that kind of bubbles up. And so in some ways, each one of my poems is a bit like a portal for me into that, because I’m always yearning for that other world because, you know, we could die of boredom in our lives on a certain level. Right? It’s like, without access to poetry and art and the kinds of things that allow our imaginations to live larger than, you know, capitalism or the jobs we have or whatever it is that keeps us living small lives. And so, in a way, my poems are like portals, like the windows that I’m looking through. I guess the window becomes the interface of my yearning, yearning to reach past the mundane materiality of what I’m surrounded by.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

In turn, I wanted to ask you more generally about how poetry as a form of art or as a discourse that is outside of capitalism and mass-cultural spheres, can address our growing worries and our desire for other forms of conversations?

What draws me into poetry, what draws me into the language of poetry, is the remarkable ability of poetry to confound the conditions of possibility. In the idea that we’re born into conditions of discourse that we are required to adopt in order to be legible to the world around us, poetry, I think, affords so much—elasticity, with the templates and conventions of language, so that other possibilities can emerge in a poetic form, uniquely, singularly. The other thing that I love about poetry is that something actually happens. There’s many different kinds of poetry, but the poetry that I’m drawn to is poetry where the transformation of the poet—you re-experience it when you read the poem. These are the greatest poems in some sense, where the transformation of subjectivity that the poet encounters through language is recorded. Reading the poem, I’m able to have an embodied relationship with that sense of transformation. And that’s magical for me.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

It is so magical as a reader to experience this musing of the speaker, the experience of introspection, of solitude that can be shared through poetry. It’s so important because suddenly it becomes this space of possibilities. Unexpectedly, you see the suburb differently or this questioning about the world differently, because you enter in a sense another house, you enter another world, and you enter the space of an intersubjectivity. I completely agree with that vision of the poetic experience.

In the poem “The space between”—that’s partly what I’m reaching for, the idea that language is necessarily a shared condition, that it doesn’t make sense unless the meanings are communal. And so, despite the fact that poetry emerges often from solitude, there’s still that shared condition of meaning.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

Let’s talk about your aesthetics because it seems to me that you build your poems as a cinematic experience. The reader enters the text like a scene with many close up and slow motion frames, soft lights, the diverse sounds of domesticity and the affects of the poet. This often peaceful scene is then disturbed by a question, a worry or a strangeness. This tension gives a very interesting dynamic to your poems. This kind of quiet unrest is a prominent aspect of contemporary Canadian poetry as well. Can you talk about your writing process and how do you build the scene of a poem? How do you enter as a poet in the scene at first?

It feels like a curse sometimes, but if I don’t get to the end of a poem on its first draft, I’ll probably never finish the poem. I know wonderful poets who will work a poem line by line, you know, and they’ll go away and they’ll come back weeks later and add the next line. My poems almost always have to be born whole like Athena from Zeuse’s head. I may spend the next ten years—and a surprisingly large number of my poems take a long time like that—working on it and changing and transforming it and trying to help realize what was happening in that initial moment. But they have to be born whole almost, and then it’s a very long process of spending time inside that poem. I realized at a certain point, that when I’m working on a poem I’m spending time in memories—it’s a luxury, immersing myself into these tiny vignettes in my life—but it can also be sort of disturbed after a while, too, because often poems emerge from energies of crisis. More often than not, I would say: there’s a kind of crisis that emerges and all of that strangeness, as you say, that strangeness threatens to disrupt the stability of the cinematic scene. So that’s how I would describe my process. In a sense, the poem doesn’t start until I’m already in the scene, that’s where it starts—I’m already there, in that place, and then I’m trying to make sense of whatever that sense of rupture is that I think I’m experiencing.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

Well, to build on this and this is the second part of my question, when does the poetic discourse change and the critical distance intervene? Because I find that often there is this shift in your poems. There is a scenery, there’s a memory, there’s a portrait of something, and then there’s a shift into a thinking mode, or there’s some kind of a critical distance intervening. There is this tension and it is very interesting. But does this tension happen spontaneously or is it something that you work on afterward?

No, not at all. I mean, your question makes me want to go back and read the manuscript to look for this shift! What it makes me think though, is that the poem is my attempt to reconcile a tension. I’m thinking of this poem that isn’t in the new book—in fact, I think I may have lost the draft. I was sitting in a cafe one day working. And there was a giant dragonfly trapped in the restaurant. And for the entire two hours that I was there working, it was desperately trying to get out. And it couldn’t. And whenever it came low enough that I could see it, it was clearly withering away, it was desiccating, it was probably dehydrating. It was dying. And so, for two hours, I shared in a way, a superficial way, but I was very aware of this dragonfly’s, you know, it’s struggle for life against the window or whatever. It was so moving. I mean, it’s the smallest, silliest of things. It’s an insect. But I was so deeply moved by this incredibly epic struggle. And then my own subjectivity—it was like, should I save it? How silly will I feel saving a dragonfly in a crowded restaurant, you know? All of that conversation happens. I think maybe what that critical shift is, is that on the one hand, I want to capture in the poem all of that weirdness. And some of that’s just learning to be a good writer. I want enough and the right detail. I want to capture the pieces of that scene, to bring somebody into that scene with me, and then trying to reconcile the mess of energy that, whatever it is, has evoked in me. So my hope is that it wouldn’t only happen through a critical intellect, but also through the poetic possibilities of language—that the poetic possibilities of language offer a more enriching, a deeper and more confounding way to understand, rather than the traditional epistemology of logic and reason.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

In this collection there is an uneasy speaker and sometimes I would add a voyeur, who is often mis en scène thinking, reminiscing, musing about the small beings (insects, animals), about small moments of life, trivialities, and of course greater topics such as social injustice, climate change, death, etc. And we feel that the poems, the poem’s role in a way is to knit all of this together and to resist to “A falling of things”, which is the title of one of your poems. Would you agree that the role of the poem, of poetry, would be, in a way, to resist the “falling of things”?

That’s a very astute reading of that poem and of the collection. I can’t say for all poetry, I mean, I can only say for the kinds of poems that I write, that I’m striving for. I’m caught in a life with a lot of small things, small events. So I’m reaching. I’m trying to reach past because I distrust the materiality, the simple materiality of the world that we live in. You know, at a certain point in the Western world, a lot of us threw god away. So we no longer had that kind of a cosmology to situate ourselves within. We were left with science, right? We were left with science and reason, science and economics, science and capitalism. And it’s not enough. I don’t think the material production of what I’m surrounded by and all the relations that that demands, and all the lives that it destroys, and I mean all the – you know – all the complications with capitalism, I don’t think that’s it. It’s like the poem from the book ‘Artist’s statement for found sounds at the lake’, I don’t have a God I can go to, I don’t have a religion that I can go to. But I do have a sense that there is something more magnificent and magical, something more going on. I’m always trying to reach through the falling of things to try to touch whatever that essence is out there that I have trouble naming in so many ways.

Dr. Michael Lithgow

Dr. Evelyne Gagnon

And I have a last question for you, let’s talk about this ravishing title: Who We Thought We Were As We Fell. I can’t help but thinking that this title resonates with what we have been through personally and collectively since the beginning of the pandemic, maybe because it gave us more introspection time or maybe because so many illusions fell apart. How did these tumultuous times influence the making of your collection? Do you feel your title resonates with the times?

So the work on this collection was completed in the months leading up to the beginning of the pandemic. There was some overlap in the final finalizing of the manuscript and getting the poems in the final form that happened during those early months of the pandemic. The title itself, it’s an interesting story. The publisher had their heart set on a very different title, one I didn’t like much. At a certain point in the pandemic, I woke up one morning and I said, I’m going to write the publisher and I’m going to ask them to change the title. It was partly because of the pandemic, and how the old title no longer felt appropriate at all, and the new title opened something up. So I did, I wrote the publisher, and they went with it.

The phrase ‘Who We Thought We Were As We Fell’ comes from a poem about falling out of love in a way—in that intense magnetic, romantic sense of love—and the idea is that who we think we are when we fall in love shifts, when we start to fall out of love. The idea of “falling” in love is that there’s an absence of agency in there, like we don’t have control. When that shift happens, when that electric magnetism begins to fade, sometimes it begins to fade, suddenly we have control and there’s an agency that we have.

Thinking about this in the wider pandemic context, I think we get caught in a variety of situations as human beings where we’re falling. Maybe we’re falling up or maybe we’re falling down, but we’re falling, and there’s a way in which our understanding of agency in the relationships gets lost, and in that out-of-control feeling we can imagine something that’s very different from what we think when we return to places of agency, or places where we think we have agency. I think our understanding of our own subjectivity shifts. It’s a moment of enormous potential and of enormous risk. I think it’s all sort of embodied in that moment. It’s like the moment—have you ever been in a pool, maybe as a kid, and the bottom of the pool is angled and slopes to the deep end? And you start to slip. You start to slip down the slope. And you can’t stop yourself, you’ve lost control a little bit, not quite, you’re not sure. Something emerges in that space. Maybe it’s like that with the pandemic, we’ve lost control—of so many things, but maybe of who we thought we were— and in that instability, other imaginative possibilities can emerge.

Dr. Michael Lithgow