Opinion: Accessible design certification an ‘eye-opening’ experience for AU architect

Dr. Henry Tsang, an award-winning architect and Athabasca University (AU) professor, recently completed the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification Training (RHFAC). He shares this review of the course, which he says “renewed my commitment to building a more accessible, equitable, and inclusive world.”

I recently became a father. Since I started moving around town with the baby stroller, I have come to realize the challenges and barriers in navigating the city and our buildings with wheels. How do I go upstairs without a ramp? How do I open a door and keep it open? Where are the universal bathrooms? And perhaps most importantly, where are those darn diaper-changing tables when you need them?

As an architect, I spend a lot of time thinking about buildings, and how to design them to be better adapted to the users’ needs. However, I’ve become aware that accessibility has been a blind spot in my design process.

“I’ve become aware that accessibility has been a blind spot in my design process.”

Accessibility is not a topic formally taught in an architect’s training, so for most designers, it is merely a requirement of the building code. For instance, the code requires minimum-sized universal washrooms to be included in public buildings but there is no mention that they need to be easily found or accessed. Unsurprisingly, they aren’t.

Dr. Henry Tsang with his toddler, Issey, in front of a staircase. (Supplied)

Discovering my blind spots

To fulfill my professional continuing education this year, I enrolled in the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification Training offered through PowerED™ by Athabasca University. To be honest, I started the course not expecting to learn much. After all, throughout my 15 years in practice, I designed several hospitals so I thought I already had a good grasp of what would be needed to design an accessible building for wheelchairs—requirements such as room dimensions, door widths, counter heights, ramp slopes, and hand rails.

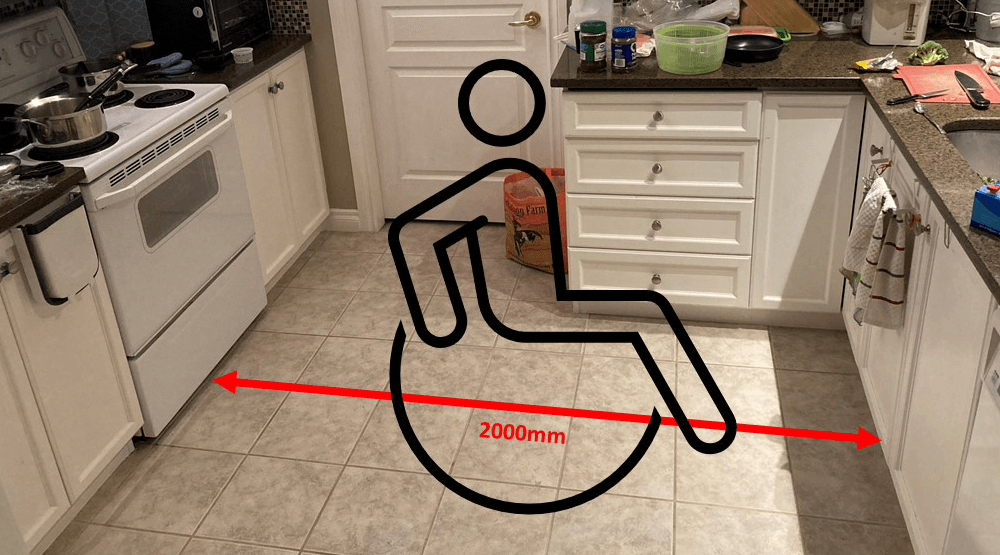

I had only scratched the surface. Through the intensive and interactive three-month course, I learned how to see space through various perspectives that are different from the “standard” person that buildings are designed to fit. The average building is, in fact, a one-size-fits-all that doesn’t work for everybody. A tall person may need to slouch to go through doors and a small person may need a step stool to reach the kitchen faucet.

What else? The international symbol for access is a man in a wheelchair, and that is also problematic. I never really paid much attention to the banal blue sign mounted in front of toilets, but I found out that designing a building for the “wheelchair guy” makes accessibility centred on mobility and excludes many. What about people with visual impairments? Hearing impairments? Invisible disabilities? Seniors? Parents with strollers?

Made for industry professionals

The course is custom-made for professionals in the construction industry. It is to the point, so I believe it is an essential course for colleagues working on accessible buildings. It gives a comprehensive description of the design and construction phases, documentation, regulatory environment, and human rights legislation related to accessibility.

The course then dives into all the different areas of the building that need to be flagged for potential barriers. This starts from the site access at the parking lot or transit station to the path to reach the building entrance. Moving inside the building, all the circulation paths must connect to every programmatic section of the building. To help people of varying disabilities, important visual, audible, and tactile features are also introduced. Relevant suggestions are also provided to improve usage and layout of functional rooms, such as the sanitary facilities and spaces for work, life, and play so that everyone can enjoy them equally.

“Designing for accessibility is not about making buildings usable to a larger minority, but rather about making buildings enjoyable to all.”

After completing the course, I am now able to use the RHFAC rating program to evaluate a building’s accessibility. But what makes this certification program unique is that the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification is not a checklist but rather a holistic assessment of the users’ experience. I realized that designing for accessibility is not and should not be a prescriptive process. It should be one focused on the physical, sensorial, and emotional experience of being in buildings.

Designing for accessibility is not about making buildings usable to a larger minority, but rather about making buildings enjoyable to all, and in which everyone feels welcome and included. As one of the instructors put it: “Design for accessibility and inclusion will follow.” The RHFAC training course has truly been an an eye-opening experience, and renewed my commitment to building a more accessible, equitable, and inclusive world.

Banner image: Marcus Aurelius from Pexels.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and may not reflect the views of Athabasca University.